THe Hammer ~ The King of the tools

The hammer, such a simple and unsophisticated tool, has refused to evolve for thousands of years. There have been many different shapes and sizes, different metals used, and different materials for the handles, but overall the design of a mass and fulcrum has never been improved upon.

The hammer is the King of the tools because with it, every other tool requiring a metal part, for every other craftsman and trade, can be made. My obsession with hammers began when I started to shift my focus from the end product to the tools, the processes and techniques. Hammers are to a blacksmith what paintbrushes are to an artist. Some are for changing the landscape, others are for fine detail or capturing specific shapes. They are the positive shapes used to create the negative shapes you require.

When you understand the blacksmith's hammer technique, then you will start to notice the various personalities hammers have and the way they behave. Blacksmithing is the only craft I know of that grips the hammer in the middle of the handle. Many smiths would disagree, but this works for me. I use a loose grip in the centre of a 10 inch handle, two fingers one thumb, so that when the hammer swing completes it's arc, the hammer shifts forward in the hand and there is a final whip-crack motion of the hammer head, creating more momentum and more impact. The loose grip allows for great rebound, which halves your workload, as you no longer have to lift the hammer. A great visualisation of how loose the grip should be, is to imagine you are throwing the hammer, then catching it on the rebound. Accuracy is linked to your elbow. Keep it close to your side and the hammer falls in the same place. Power comes from lifting the hammer above your head, utilising the ball and socket joint of your shoulder.

For forging, a compact head is great as the hammer will rebound straight back up with very little wobble (less lifting of the hammer, less muscle fatigue, less grip strength required to keep the hammer face on target). Dog head hammers forge more aggressively with all the weight forward of the eye. But they are harder to lift and rebound less well. Dog head sledge hammers for example, are designed to fall to the side after a strike, which is a useful feature when working with teams of strikers. The longer head hammers used for armouring tend to have increased wobble on the rebound, but much of this is negated by the fact armourer's don't tend to take full swings - it is mainly a wrist action for shaping sheet metal. Forging is all about impact, whereas sheet metal can be more of a stroking action, like planishing. The different trades have different requirements from their hammers. Blacksmithing requires dressed (no sharp edges) faces for the most part, whereas stone-masonry requires a sharp edged face to split the rock.

For craftsmen, and particularly blacksmiths, hammers are a legacy to be passed down. Usually a craftsman's tools are the only thing left in his workshop, all creations having been sold, and scattered to the four winds. This is part of why I believe that making my own tools is essential. They are the only aspect of my work that will be left when I am gone.

Spade forger ~ One man's quest to dig up the past

Of all the things i'd find fascinating, I never thought digging tools would be one of them. My interest sparked when I acquired a hammer from a retired French blacksmith. This blacksmith or Forgeron specialised in forging spades. This hammer was constructed in such a way that it stood out as unusual from first inspection. The body was wrought Iron, and the working faces had been added much like you would make an axe- the iron had been cut with a chisel, and steel inserted for the hammer faces, then firewelded shut. To date it is the only hammer I have seen with steeled faces attached this way.

But the mystery didn't stop there. The hammer was a cross pein type, a directional tool for forging, and had large convex faces, which tend to leave few deep marks but spread the metal nicely in the direction you wish it to go. It was not for simply shaping or curving sheet metal. It was for thinning out much thicker metal. And herein lies the key to spade forging.

Modern spades are usually cut out from sheet steel, be it spring steel or mild, stainless or carbon steel. This spade template is then curved to shape, but it isn't forged - a machine presses the shape. The result is a spade of the same thickness of steel at every point in it's construction, and this is not a good thing. Spades have to be very tough, they are levered about just by virtue of the way they are used. Having thicker steel at the point where the socket meets the blade is essential. Spades also have to retain a degree of sharpness - for cutting through tree roots and the like. Therefore being able to control the thickness of the steel is necessary to later adding a bevelled edge- something you can't do with thin sheet metal. A differential heat treatment ensures a sharp edge and very tough body. This is another step mass produced spades fail to master.

At one time in England, all spades were hand forged. And it should go without saying that included forks and shovels, in a huge variety of patterns and sizes, some for specialist tasks. With the Industrial Revolution, the number of handcrafted spades, however, has been on the decline. So much so that the craft is classed as "Critically Endangered" by the Radcliffe Red list.

Forging spades the hard way is very rewarding, there is a satisfaction to be had in a well constructed tool from one piece of steel with an integral socket. I have been acquiring surviving examples of rare specialist spades and forks for my museum, which you can see in the pictures below. Being able to inspect the construction of a hand forged spade is a huge factor in recreating the techniques used in the past.

Below is a photo of the hammer that started it all, some examples of specialist clay spades, hand forged forks including the largest fork in the midlands, and a Forged Coke shovel.

This is a local smithy ~ for local people

Without trying to sound like a comedy sketch from The League of Gentlemen, I have started accepting commisions from locals on the basis that they are either a repair, refurbishment, or a tool that needs forging. I wanted to challenge myself in new directions whilst meeting the needs (rather than wants) of my community, and perhaps the best side effect of this decision was it gave people the experience of a village smith that is actually useful and affordable - a rare thing these days.

My last repair job for a local man was to repair an old wrought iron gate, likely made by a village smith in the late 1800's. This gate was from a historic grade 2 listed cottage, and as such it had to be a repair faithful to the original construction, strong yet simple, and I felt it was important to be able to distinguish which parts were new, from the old.

The original iron gate hinges had perished and broken. I forged new ones from mild steel and hot rivetted them to the back of the gate, rather than remove more original material to splice in a new piece. This makes it obvious to anyone which parts are original and which are modern repairs. I was happy with the request as it was a new task for me, but not outside of my ability.

"It's alive!" ~ Crafting the franken- apron

Crafting my own apron was an idea that had been nagging me for two years, so I finally tackled it head on. Modern blacksmith aprons are full length and hang from the neck, and this seemingly small amount of weight over time seems to quantify, leading to bad posture. Looking at photographs of blacksmiths from the early 1800's, the aprons all had one thing in common- they hung from the waist. Some would argue that a half length apron of this type is a Farrier's, and in modern times that is true. However, before Farriery became a separate craft in it's own right, nearly all village smiths shoed horses as a large part of their income.

One of my favourite Medieval poems, 'A complaint about blacksmiths' provided some descriptive insight into Medieval smith's aprons; it states they were made from a bull's hide and "Shackled against fire-finders" (sparks). With this in mind I forged my own metal hardware for the apron including 'shackles' (small iron rings to attach straps) and a small horseshoe, which I intended to hang the traditional way, with points down (points up is a modern mis remembered tradition to my mind).

A hide of scrap leather from a car boot sale formed the main body of the apron. An old leather jacket collar formed the waist, and I took apart an ancient shire horse bridle for the belt, cleaned and oiled it, then replaced all of the rotted stitching. The stitching on the apron took me quite some time, and really wasn't kind to my fingers (I should find a thimble), but I was well pleased with the result. I reinforced any areas where stitching wasn't enough with solid iron rivets. I named it the Franken- apron because of all the stitching and pieces from different things cobbled together. Although Frankenstein was the scientist, not the monster...

restorations ~ the jack of all trades

Here are two blade restoration projects I took on as part of providing a service to the wider community. My Father was an antique furniture restorer so I grew up with some insight into sympathetic restoration. The real trick seems to be to not overdo it.

The first was a very well made bushcraft knife by A Wright & Son Ltd Sheffield, which belonged to a local landscape gardener. This knife was a tool he used every day in his work, but sadly it got lost under some bags of cement in the back of his truck and was not found again for several weeks. The knife was covered in cement, there was fairly deep rust pitting on the blade and the sheath had gone mouldy from the damp. The blade I cleaned up with a scotchbrite wheel which returned it to bright steel without removing any metal. For the handle I used a softer cloth buffing wheel, which didn't remove the original patina. The sheath was cleaned with non mildewing tung oil, which darkened the scuffs for a uniform finish, then I re waxed and polished it. The scandi grind had a re sharpen on 5,000 then 10,000 grit whetstones, which removed most but not all of the pitting (A little pitting would serve as a good reminder not to lose it again, and it was a part of the knife's story).

The second restoration was a Kukri from Nepal, owned by a gamekeeper and also used daily. The handle scales had become loose over time and the owner wanted the issue addressed before it became a problem. I took the scales off (intact) with a craft knife and some gentle tapping on the pins with a centre punch. Sadly some glaring flaws had been hidden by the maker beneath the handle scales. The guard was welded on and disguised to look integral (forged from one piece), there were gaping holes in the guard, the tang of the blade was not flat, but full of depressions where a grinder had been used with no care. The pins were soft aluminium and badly misshapen. The tang holes were different sizes and countersunk from one side.

Undeterred, I removed all of the old epoxy from the scales and tang; I found a sharp woodworking chisel used in a scraping motion did the trick. An acetone bath removed any residue of oil etc on the surfaces prior to re gluing. I re drilled the pin holes in both the tang and the scales to take slightly larger, solid brass pins. I then filled the gaps in the ill fitting guard with a metal epoxy. The scales went back on with plenty of new 24 hr araldite, then I cut the pins to size, filed them down and buffed off all surplus epoxy with the scotchbrite wheel. To freshen up the handle patina I dyed the wood scales with Walnut dye and buffed them on a cloth wheel, then added wax. You can see the results below.

Keeper of the flame ~ The Blacksmith in Folklore

“The artisan is a connoisseur of secrets, a magician; thus all crafts include some kind of initiation and are handed down by an occult tradition. He who 'makes' real things is he who knows the secret of making them.” -Mircea Eliade, The Forge and the Crucible: The origins and structure of Alchemy.

It is common knowledge that blacksmiths are a secretive lot.

This trait has continued from ancient times to the modern day in different forms, and it seems true to form that someone involved in the creation of objects, wrought with intent, imbued with identity and skillfully executed would be possessive over their hard won knowledge. In ancient times guilds kept trade secrets and also ensured they were passed on. Some guilds still exist today, one of the more notable being the French Companions of Duty, a guild with medieval roots.

Below: A French 1700's farrier's driving hammer, highly decorated and belonging to a member of 'Les Compagnons du Devoir' (The Companions of Duty), engraved with a square and compass.

Delving into traditions associated with blacksmithing often leads to a wealth of folklore tales which claim that magic is intrinsically bound to the blacksmith. And it is hardly surprising considering they could conjure metal from rock and fashion it into useful tools and beautiful objects. The forging of tools was seen as divine, and in contrast; the forging of murderous weapons seen as demoniac, creating a unique dichotomy associated with the craft.

Working with Iron in particular has many folkloric associations; Iron repels negative energies, ghosts and demons (most likely due to the sulphur content). The word blacksmith means black smite, or, to smite (hit) the black iron. To forge means to create something strong, enduring, or successful.

Blacksmiths were known to be great healers in medieval times. Medieval smiths often fulfilled the role of a modern dentist, pulling painful teeth with their pliers. It was also believed that a blacksmith had the ability to heal by touch, much like royalty. Other traits included giving illogical advice which hinted at a smith’s knowledge of the hidden realm. A recurring tale in folklore is that of a changeling who has stolen a newborn baby and taken it's place, and only the village smith knows of such things and how to remedy the situation to see the child's safe return.

In contrast to these benevolent tales, blacksmiths in folk tales often made pacts with the devil, and ironically the smith usually came off better in the stories. For example blacksmiths are the only craftsmen who can do work for the devil, like shoeing his cloven hooves with ox shoes.

Blacksmiths also have a strong association with witchcraft. Proof of this can be seen in an 8th Century hymn to protect people from the “spells of women, smiths and druids”. Despite these associations with witchcraft, blacksmiths largely were not persecuted by the church, because they were too useful to kings and peasants alike.

The spectacle of a forge being worked without modern electric lighting is likely to have an effect on naturally superstitious people. The flames appear to make the shadows dance, and the four elements are brought to bear; wind from the bellows, fire in the forge, earth in the form of coal and iron, and water in the quenching trough (medieval blacksmiths were also called burn waters due to the constant hiss of hot iron being quenched in water). The medieval poem, “Complaint against the blacksmiths” describes the smiths as “Cammede kongons” (crooked changelings) Who “Spell many spells”.

If there is one thing all folklore concerning blacksmiths agrees on, it is that it would be wise to stay on the good side of a blacksmith. Hands that can cure people are also capable of cursing them.

Also known as “Turning the anvil”, the blacksmith’s curse is a particularly malevolent thing to do. One Irish folk tale says the blacksmith could “do any enemy to death by turning the anvil on him”. It goes on to describe a landlord that was found dead at the exact hour of the “turning of the anvil”. It claims that his skin was all blackened and that there was no doubt that he had been “done to death by the curse”. To enact the curse, the smith turns his anvil widdershins (in Irish “Tuathal”) -Anti clockwise- until the horn points directly east, and then utters the words of malediction.

Below: A 1700's English coachmaker's anvil, decorated around the feet with half moon stamps to "Ward off evil".

The theme of moving the opposite way to the sun's trajectory has deep connotations with fairies and the hidden realm. It could be argued that Tuathal, Gaelic for "Left, North" or counterclockwise, is reminiscent of the Tuatha Dé Danann, or tribe of the Gods, who later became the fairies of folklore. This would imply that the smith's power to curse or to cure is not intrinsic, but exists in the form of allies in the hidden realm.

Other curses or spells involve the forging of nails, and similarly some “cures” involve a horseshoe, which everyone knows are lucky. Hung points up, they retain their luck, hung points down above the hearth, they empty their luck into your home.

Quest for the Moldthur King's hammer

*The following is for entertainment purposes only, though there are truths in this story, they are expanded upon to add to the folklore ~

Every dedicated blacksmith needs a quest; for some it is the perfect steel. For others fame or notoriety. For me it was a mythical hammer, a Mjölnir of my own.

This is the tale of my quest for the Mythical hammer Gawr Madoc, wrought by Dwarves for the King of the Moldthur, a race of earth dwelling giants. Legend has it that the hammer was forged to one day awaken the sleeping giants that were turned to stone, forming Albion’s hills. This can only be achieved by striking the hammer’s counterpart, an anvil which remains lost to this day.

I first heard about Trollstep Mine as a Rumour, the locals said it was different from most mines, the craftsmanship at the entrance of Archaic design, not hewn by man’s hands.

This didn’t deter men from entering and exploiting the rich seams of ore found deep within, but not without a hefty toll. The mine became known for bad luck. Deaths, floods, cave ins and mysterious disappearances were common. The intrepid Miners discovered a Forge at the lowest level of the mine, down in the very bowels of the earth, and more importantly, a hammer that had not aged a day, whilst all other iron tools around it crumbled to red dust. Miners being superstitious folk, they left the hammer where it lay.

After years of research and consulting old musty volumes on mining written in the 1600’s, I thought I finally had everything I needed to find the hammer. Including a spidery map of the tunnels and levels of Trollstep Mine.

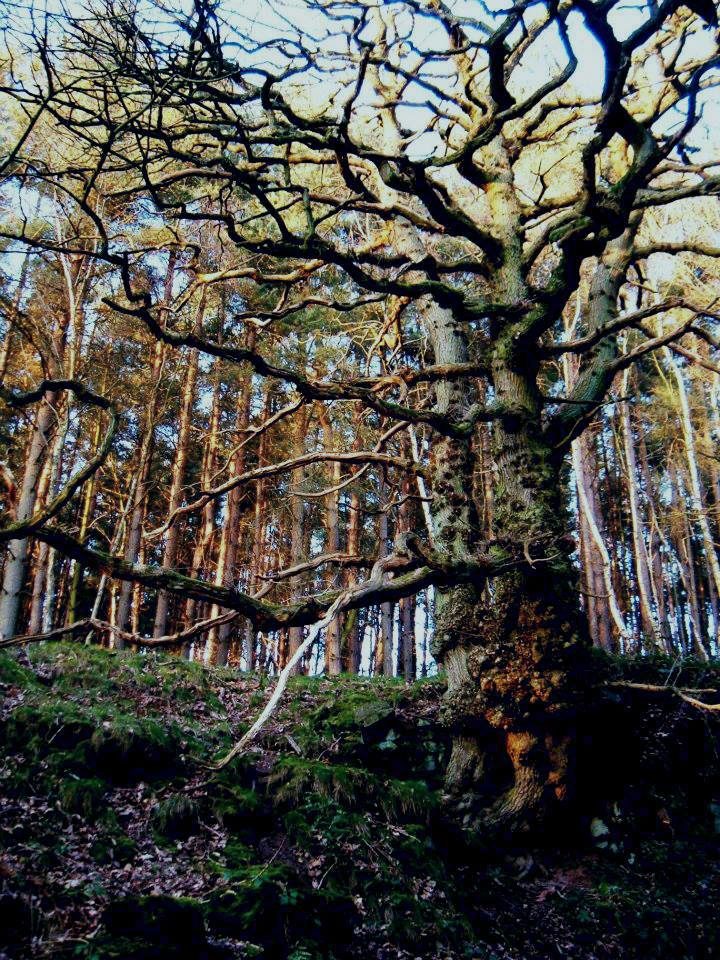

My quest began one winter morning when I ventured to Trollstep wood. Once amongst the trees I began to notice strange tracks in the snow made by neither man nor any beast I knew of. They were elongated and with three clawed toes. The wood was deathly silent, the surrounding hills were shrouded in sleety mist, hiding the sun. As I gazed out at the snow capped peaks, my breath making a plume of smoke in the chill air, a chorus of hoarse chuckles and guttural barks echoed from the cliffs above, sounding as if they possessed a great secret - that the daylight would soon be spent. It was a more unnerving sound than a Vixen’s scream in the dead of night.

Not wanting to linger in this place, I sought out the ancient Oak Tree which grows near the northern edge of the wood, my goal: to steal it’s beating Heart, without which any lone adventurer in the mine would be swallowed up by the dark.

Once the heart was in my possession I made my way west and warily descended stone steps into Trollstep mine, the hackles on my neck rising in the damp draft exuding from the entrance, as from a living being with fetid breath.

Taking care to safeguard myself from the numerous manifestations that inhabit Mines and Mountains- Kobolds and Knockers, Blue caps and Old cutty Soames, Trows, Gnomes and Boggarts, I proceeded ever deeper, sometimes walking upright, sometimes crawling on my stomach or climbing down a vertical shaft, my body became swiftly covered in wet reddish mud, my mind conjuring all sorts of unspeakable horrors waiting for me in the black.

After what seemed days, but was more likely many hours I found the forge. All around was saturated with soot, objects that must have once been hammers and sledges lay where they had been dropped. The bellows had long since lost their wind, the wood perished and leather rotted.

Amongst the debris one object stood out, untouched by the ravages of time and the acidic environment. The hammer I had been looking for. It had a domed face to either side, with a strange spiked pommel or counterweight at the opposing end to the head. The handle had a dark green ichor seeping from it. Gingerly I hefted it, marvelling at the weight of the thing, and replaced it with the oak tree’s heart.

Leaving the mine would have been worse than entering; there was a palpable feeling of being followed as I sought to retrace my steps and escape the oppressive blackness, but with the hammer in my grip, I felt a strength that kept waves of panic at bay.

Finally I staggered out of the mine, into a dark and stormy night. The wind seemed to whoop with joy at my reappearance, its fingers snatching at my sodden clothes and hair. All around in the darkness, pairs of red eyes peered at me from the treeline. The guttural barks rose in a dreadful cacophony at the sight of me. As if in answer, a nimbus of foxfire flame burst around the hammer and it began to resonate with a keening wail like a banshee. The barks ceased and the eyes winked out, leaving me to make my escape unhindered.